|

|

|

Follow Mark on Facebook for more stories |

||

|

|||||

|

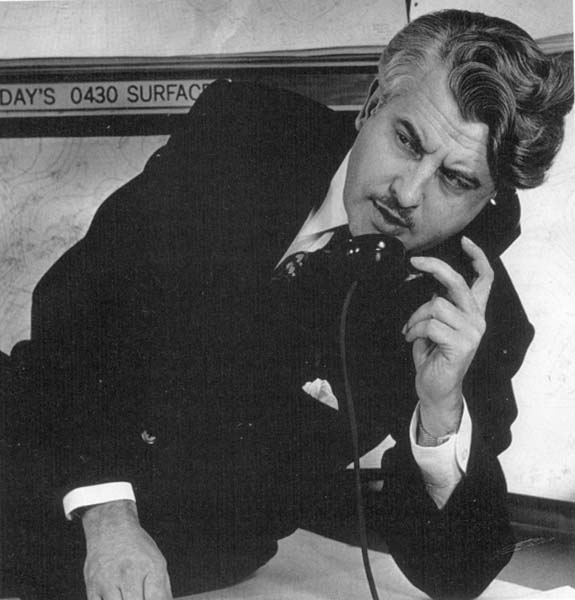

Tahoe Nugget #177: Snow-starved Olympics Need Irving Krick While most of the nation has been focused on the epic snowstorms and blizzards that have plagued the major mid-Atlantic metro areas like D.C., Baltimore, and Philadelphia with their snowiest winter on record, it's been quiet here on the western front. After a healthy start, water content in the Lake Tahoe and Truckee River basin snowpack has slid to below normal for the date and the forecast calls for fair and mild weather well into next week. Yesterday (Friday, Feb. 12) I had the good fortune to be a guest on Capitol Public Radio (Sacramento's NPR affiliate) for an interview about my new book, "Longboards to Olympics: A Century of Tahoe Winter Sports." Click here to listen: www.capradio.org/programs/insight/ The same El Nino event in the Pacific Ocean that has enhanced the East Coast pipeline of strong winter storms has denied some of the 2010 Olympic venues much needed snowfall. Interestingly, 50 years ago organizers for the 1960 Winter Games at Squaw Valley had their own bit of weather trouble. In late 1959, persistent high pressure had kept the region bone dry. With the eyes of the nation and the world on Squaw Valley's weather and with no Pacific storms in sight, Olympic organizers were getting nervous. Native Americans from western Nevada were brought in to perform snow dances, but no luck. Fortunately, a professional weather forecaster from Southern California named Irving P. Krick was on the payroll. Krick was one of the first widely-known commercial meteorologists in the United States. The U.S. Weather Bureau and American Meteorological Society (AMS) both considered him a fraud. Krick was also an early proponent of using silver iodide particles for cloud seeding. Irving Krick had been named the official "weather engineer" for the Winter Olympics, in part because he had provided a forecast for February 1960 two years earlier, specifically singling out that the second half of the month was the best time to hold the Games. He also promised that if mountain snow depths were inadequate, he would come to the valley and produce what was needed. The Northern California chapter of the American Meteorological Society, who had tossed Krick out of their organization prior to the Winter Games, notified the Olympic Organizing Committee of their "concern and displeasure" with Krick's appointment. They warned that since the rogue weatherman was not a member of the AMS he was not bound by the Society's concept of professional ethics. The AMS called Krick's long range forecast two years before the Olympics a "scientific impossibility" that did professional meteorology a disservice. In preparation for the possibility of poor snow conditions, Krick had positioned 20 ground-based cloud seeding generators around Squaw Valley. When New Years Day came and went with no snow, Krick himself was getting nervous. The Games were only seven weeks away. During the second week of January weather patterns began to look more favorable for seeding. As storm clouds moved in, Krick fired up his generators to pump out clouds of silver iodide particles that drifted into the sky and it began to snow. By January 10, more than three-and-a-half feet of snow buried the valley floor with more than seven feet on the upper mountain. Irving Krick claimed credit for the snow, but Sierra weather is fickle and cold logic suggests that the storms would have arrived anyway. Photo #1: Squaw Valley had no snow 7 weeks before start of Winter Games.

|

|||||

|