|

|

|

Follow Mark on Facebook for more stories |

||

|

|||||||||||

|

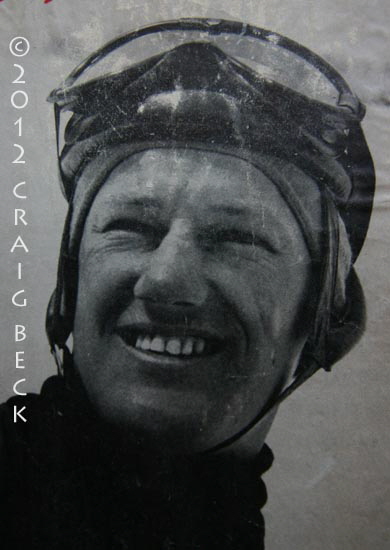

Tahoe Nugget #223: Mad Dog of Donner Summit Today's hot-shot skiers and boarders generate You Tube highlights by hucking killer cliffs, barreling gnarly half pipes, and snorkeling through cold-smoke powder. But long before the voyeuristic days of helmet cams and heli-videos, a Donner Summit resident named Dick Buek made an international name for himself by ripping steep lines and pushing the protective boundaries of sanity. People started calling him "Mad Dog." Many Dick Buek stories seem unbelievable, but just about all are true.

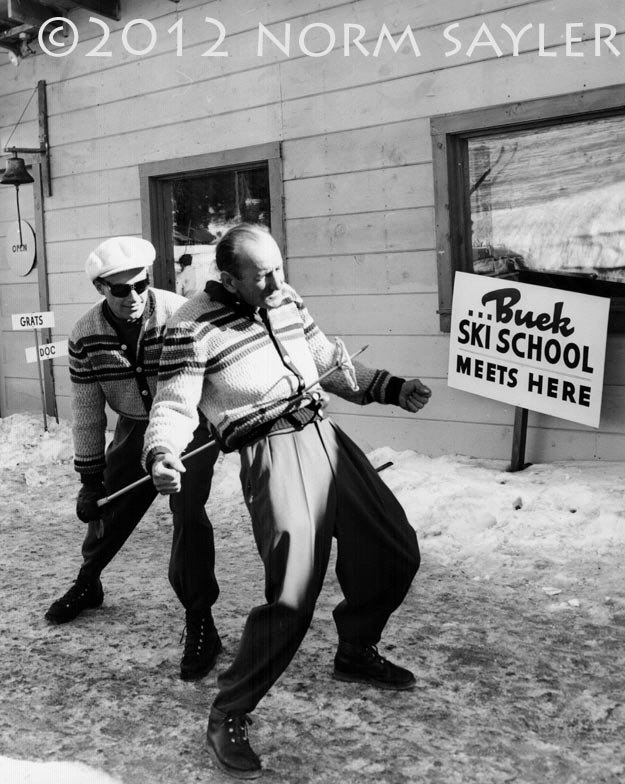

Buek, a maverick and athletic marvel, described his seemingly reckless skiing style with these simple words, "When I go, I want to go straight in." The so-called "Mad Dog" wasn't psycho. Longtime Donner Summit local Norm Sayler knew Buek well. They trained in ski racing together and were good friends. Sayler says, "Dick wasn't a crazy person. He was a very calculating young man." That may have been true, but there is no doubt that Buek was a hard charger. And not just on skis. He owned two airplanes and loved riding his motorcycle fast. Ironically, it was the cycles and airplanes that did the most physical damage to Buek, including causing his untimely death. One of the classic Buek stories was when he was riding his motorcycle in the Bay Area and an oncoming auto drifted into his lane. It was one year after he had won the 1952 U.S. National Downhill. A heavy fog obscured visibility that May evening and Buek hit the car head on. Unconscious and unresponsive, Buek was given up for dead and a sheet pulled over his sprawled body. Shortly after, however, a highway patrolman recognized Buek's face and determined that he was still alive.

In the emergency room, doctors found that virtually every bone on the right side of his body was broken, including his arm, pelvis, leg, and ankle. His knee was completely shattered and his spleen ruptured. The doctor later told Dick that he would be lucky to walk again, let alone ski, but Buek told him that he was already late for getting into shape for next ski season. The following winter he began his rehabilitation by skiing on one leg with half his body in a plaster cast. Despite painful therapy, his right knee was so damaged that Buek regained only 60 percent mobility with it. Metal pins held him together, but in 1954 he entered the U.S. Nationals at Aspen, Colorado, where he took first place in the Men's Downhill. Despite his physical obstacles, Buek won two national downhill titles, was second a couple of times, third once and fourth once. His third place finish in 1956 occurred after he had broken his back twice since the motorcycle crash, and was skiing with a full metal brace.

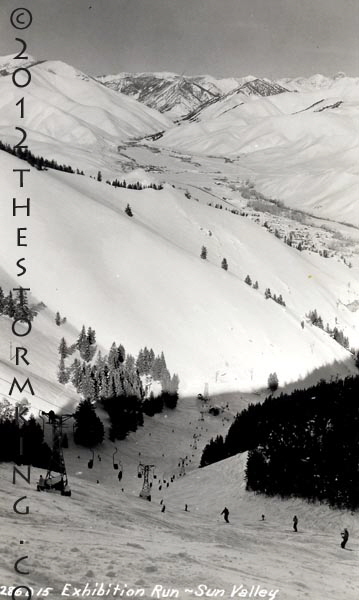

Buek was in a class by himself. The first time he saw Sun Valley's double diamond Exhibition Run, he schussed it without turning — something no one had done before. The first, and only time, he tried a professional ski jump, he won the competition. Buek also claimed to be the first person to schuss Headwall at Squaw Valley. In essence, Buek's skiing style was to hit the slope, no matter how steep, bumped, or icy, and schuss straight down in a partial tuck, at blinding speed.

Dick Buek was raised in Oakland, but later his father Carl ran the popular Buek Ski School at Soda Springs on Donner Summit. Dick didn't get introduced to skiing until he was a teenager. As he grew older and bolder, he became one of the most aggressive ski racers in American history. Dick was a member of the 1952 U.S. Olympic team (slalom and downhill), and one of four Olympians to hail from the summit—the others were Hannes Schroll (1932), Dennis Jones (1936), and Jones' niece, Starr Walton (1964). Buek's extreme skiing attracted national attention to the Truckee and Lake Tahoe region, but the Mad Dog from Donner Summit also loved to perform aerial stunts like the time he flew his plane down a lift line at Squaw Valley, beneath the cables, banking around the lift towers like he was slalom skiing. It has been reported that Buek also flew his plane underneath the Rainbow Bridge on old Highway 40 near Donner Pass, but Norm Sayler says that although this particular stunt probably never happened, Buek had talked about trying it. He once ran out of gas over Donner Lake and landed in the water, but boaters raced to the scene, secured the plane with rope, and managed to keep it from sinking to the bottom. In 1955, Buek fell in love with paralyzed ski racer Jill Kinmon who had crashed at Alta, Utah. They spent a lot of time together while she rehabilitated, but Jill regained only limited movement and mobility. Buek proposed marriage, but Jill was unwilling to burden the energetic young man with her physical disabilities. This heartbreaking love story was portrayed in the movie "The Other Side of the Mountain." Despite her injuries Kinmont became a teacher and painter. She died in Carson City last week at the age of 75.

Dick Buek was just two days shy of his 28th birthday when he died in November 1957 after a plane he was in crashed into Donner Lake. Apparently he was teaching his friend Dick Robarts how to handle engine stalls, when the carburetor iced up and the aircraft plunged into the frigid water at high speed, killing both men. Dick Buek died the way he lived, "straight in." He was inducted into the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame in 1974.

|

|||||||||||

|